Cash rich, time poor? Or time rich and aware of a wealth of opportunities? I’m often caught saying that you can do your trip on any bike you like, but what’s the reality? The idea of this article began easing into my mind whilst reading a book that was recently republished. Peggy Iris Thomas motorcycled across Canada, through the U.S. and Mexico on a 125cc BSA Bantam. To add to her adventure, she rode with a 125-pound Airedale dog on the bike’s rack! But, did she see any downside to riding such a small bike? Before she departed her critics hammered home the point that it simply wasn’t possible to do such a mega trip as a novice on an underpowered motorcycle. In her book, Gasoline Gypsy, Peggy does mention the lack of power at altitude but other than that….

Of course, ADVMoto readers will already know about small bike adventuring from Lois Pryce, author of Lois on the Loose and Red Tape and White Knuckles. For those of you who don’t know Lois, her first big transcontinental bike trip was from Alaska to Patagonia on an XT225 Serow. And, you’ve probably heard of Simon Gandolfi, who was 73 when he set off from the Gulf of Mexico and made his motorbike trip to Tierra del Fuego at the southern tip of South of America. His ride? A 125cc Honda.

But, the idea for this article really came together at the Horizons Unlimited Overlanders Meet in the U.K. There I met a couple of young lads who’ve broken plenty of the respected overlanding standards, and had a ball doing it. I’m itching to say that they are ordinary blokes, but I soon found out that they’re far from it. To begin with they have a huge enthusiasm for a version of motorcycle travel that many have never seriously considered, let alone put into practice. As you read on, perhaps you’ll be happy with calling them odd-bods, but don’t be surprised if you start to come around to their way of thinking.

Chatting with Ed and Nathan lead me re-analyze some of my own considerations, and that’s part of the beauty of overlanding isn’t it? Travel allows us all to test and knock preconceived ideas. For sure this duo made their solo adventures happen in their own rather unique ways.

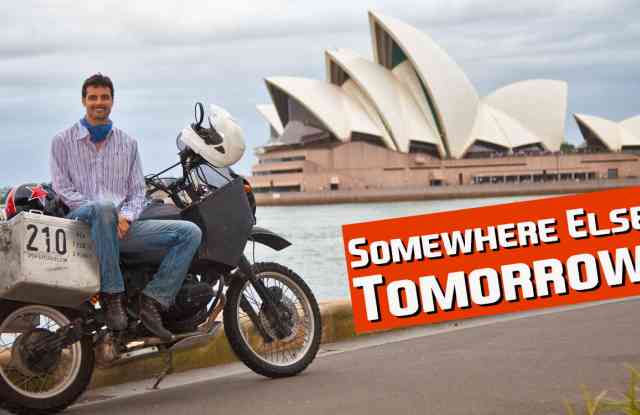

Ed March had just ridden from Malaysia on through Southeast Asia, and from Asia and the Middle East to the U.K. on a Honda C90. And Nathan Millward rode a Honda CT110, an Australian postman’s bike, from Sydney across the Himalayas, through the old Soviet countries of Central Asia and across Europe to London. A distance of 23,000 miles, taking him nine months to complete and passing through 18 countries along the way.

As we chatted I quickly became aware that they were very conscious of two key points. If they spent less on their bikes and cobbled their kit together, then the money saved would:

1. Make it affordable for them to travel in the first place, and,

2. Give them the chance to stay out on the road much longer.

But, there are both advantages and disadvantages to traveling by a small bike, isn’t there? The first that leaps into my mind is speed. Part of the reason I enjoyed my own trip around the world was that most of the time my BMW R80GS allowed me to judge how fast I could cover ground.

Nathan, on his Honda CT110, told me that he sometimes did wish for a touch of extra speed. With throttle wide open, his cruising speed was 45 mph. But even that allowed him to cover as much as 400 miles in a day when he needed to. “With the imposed top speed of 45 mph, it meant that I couldn’t race to get anywhere, and because of that I got to see and experience more, which is really what it’s about.” However, there were moments crossing the Himalayas at 17,388 feet, or riding the German Autobahns during the night time, when he really wished for a touch more than 7 HP. The bonus, of course, is that his bike was returning 100 mpg!

Ed’s Honda C90 was also only able to cruise at 45 mph, and he said, “If you’re riding around the world and everyone else is on bikes that do 45 mph, and the road surface isn’t good enough to do over that, and the scenery is stunning—why would you want to go over 45 mph?”

A bonus of small bike travel has to be the weight savings. I know I battled with the bulk of my bike on some dirt roads and there were a couple of occasions when local guys on small CC bikes shot past me looking as if they didn’t have a care in the world. And, on the occasions when I’ve ridden small bikes off-road, they have proven their point. There were some wooden bridges, for example, that my GS would have fallen straight through!

If you are planning to ride anywhere other than South and Central America, then the cost of your carnet de passage is another very pertinent point. The fee is judged, in the main part, by the value of your bike. There’s also the shipping and air freighting costs that an overlander must take into account.

Nathan gave me some practical examples. “My bike didn’t cost much to ship between various places (Darwin to East Timor by sea—$318, Bangkok to Kathmandu by air—$650), and on an Australia to Europe trip, those are two of the most expensive costs one is likely to encounter.

Ed told me that it wasn’t only the continent-to-continent costs that were affected. A small bike can often let you get into places that a traveler with a big bike just can’t. “I spent hours in Thailand trying to get my bike onto a passenger ferry to Ko Phi Phi Island with no luck (there are no roads on the island and as such no vehicle ferries). After a day of asking I was close to giving up when I decided on a new approach. I’d take my bike along into the office when meeting with the officials. The first place I went back to said, “Oh that bike, we though you meant a huge European bike!” I ended up paying an extra $4 charge for two people to lift it onto the boat over the handrail and all was well.

Weight-saving helps with another vital point for any overlander to consider; in particular the solo traveler. One of the things I feared most in my early days on the road was what would happen if I fell off the bike and it landed on top of me. If there wasn’t anyone around to help me escape I would be in serious trouble. Recently, I was reading about Nick Sanders; long-time adventure traveler. On one of his trips through the Americas he landed himself in the sort of trouble I feared. On his way across Patagonia, the winds combined with the road conditions to make life suddenly go wrong, big time. His bike ended up on top of his leg, and broke it. It started to snow and he’d hardly seen any traffic for days. Sheer guts and desperation eventually drove him to drag his broken leg out from his bike boot, which he had to dig out from under the bike. He was lucky, but still had to ride with that broken bone.

Ed commented on this, “I’ve ridden down roads that big bike riders won’t in case they fell over and couldn’t pick the bike up, I’ve even lifted my bike over fences (she only weighs 180 lbs.). And I’ve even done a test to see if I can pick her up with only one arm and one leg in case I fall off and badly injure myself with no-one around. The average “adventure” bike weighs over 500lbs….”

Nathan told me that there were other advantages of this ilk. “My bike was so small that I could easily squeeze her between a gap in the hedge in order to camp out of sight for the night.”

The guys grinned when I brought up the subject of spare parts. We’ve all heard of people waiting for weeks for simple parts for their BMWs, KTMs, KLRs, and so on. Nathan’s bike only needed a new front sprocket and regular oil changes. Although he went through eight rear tires, and one front, those tires cost less than $5 each—fitted. In Thailand, Ed’s C90 started smoking, so he decided to get an engine rebuild. A new piston, rings, valves, a carburetor rebuild, gaskets, oil change, spark plug and lunch, all at a genuine Honda garage, only cost him $43. And, it took under three hours to sort out and have the parts fitted. In another grin-accompanied comment Ed said, “I can get any engine component just about anywhere in the world for my C90, almost instantly.”

One of the key things I’ve picked up from them both is that they feel their slower pace allowed them to connect with the locals in a way that would have been much more difficult otherwise. What a bonus.

A story of Ed’s that I particularly liked was the tale of the Malaysian customs officer at Kuala Lumpur. The official was very serious and methodical. He told Ed that the task of passing the bike through customs required hours of paperwork before he’d be able, finally, to begin the inspection of Ed’s bike; the checking of chassis and engine numbers and looking through his luggage, etc. But when the customs officer saw the little C90, he said, “You’re riding that around the world? You’re crazy!” And, as soon as he stopped laughing he stamped all the paperwork and sent Ed on his way without checking anything else.

Ed told another story that really hit home. “Throughout Southeast Asia, whenever I stopped at a local’s home, or a friendly hotel, I lost count of the amount of times that I was dragged off to be shown their Honda C90 or close variant. The thing I enjoyed most was the realization, during many of these conversations, that their dream was also to ride around the world… and that their bikes were often in better condition than mine! They’d always been told they could never afford to buy the “right” bike to do it, and there I was, riding around the world on a bike just like theirs.”

Are you beginning to be convinced? Surely a cheaper bike that weighs less, drinks less, has no problem with spare parts, and is the best ice-breaker ever between the rider and the local people, has to be a go. And, we haven’t even talked about saving on the motorcycle kit. I know Nathan is extreme, because his kit amounted to not much more than a pair of Converse boots and skateboard trousers. Thankfully, a chap he met along the way kitted him out with some cast-off waterproofs—pink ones! There seems to be a significant change in pride points for these small CC overlanders.

So, how did their choice of bikes affect their adventures? The key was that they were quite happy to adapt their plans accordingly. In fact, other than some mechanical issues along the way, it appears as though they each had a stunningly good time. They rode on some of the most rugged roads in the world, and at altitudes that no sane person would be advised to take small CC bikes. Their attitude? It’s all part of the challenge, and out of every challenge rolls an adventure.

All this still begs the question, “Are small bikes better than big bikes for overlanding?” Nathan sums things up very well. “I don’t think it’s so much a case of choosing the bike best suited for the adventure, it’s more a case of choosing the bike that can give you what you want out of your journey. At the end of the day, all bikes are built for adventure. But my CT110 was very close to being ideal. With bikes, as with many aspects in life, you make do with what you have or can afford, and most of all us choose our bikes accordingly. If that’s a Harley Davidson, a BMW GS, or a little red postie bike named Dorothy, then so be it. What matters most is the way you ride it and the adventures you allow it to take you on.

Ed had a rather more pointy comment, “If the road is too straight and boring to ride a small bike on, blame your choice of road, not the bike.” Now there’s a thought. I wonder…

So, Who's Out There on Small CC Bikes?

Nathan Millward

“When people ask why I did it on this particular bike I have to be honest and say it was all that I could afford at the time. But then, when I think about it some more, I realise that even if I had all the money in the world I wouldn’t have done it on any other bike. Dorothy was perfect for most parts of the world.

“When people ask why I did it on this particular bike I have to be honest and say it was all that I could afford at the time. But then, when I think about it some more, I realise that even if I had all the money in the world I wouldn’t have done it on any other bike. Dorothy was perfect for most parts of the world.

“She was tough, reliable, and able to carry all my gear with no problem. Best of all, she blended in, and if anything drew sympathy from the strangers I met, not jealousy, which I imagine is sometimes possible on a bigger bike. It also made me feel like a bit of an underdog. People neither expected me or the bike to make it, so we had something to prove. That’s a great motivator during the times you’re thinking of giving in.

“For me, the journey from Sydney to London was all about taking off and getting lost for a while. I was in no real rush to get there. I didn’t have much money, I didn’t know much about bike maintenance, I simply wanted to take off, have an adventure and let go of the real world for a while.”

Nathan is the author of a book called Riding Dorothy, and it’s a gem. You can find out more at ThePostman.org.uk. Nathan has also just completed riding Dorothy across the U.S.

Ed March

“I love my Honda C90. Not because she is different, but because she is the world’s most popular motorcycle. This means two things; the first is the reason why she is the world’s most popular bike. The original design spec for the C90 said that it must be able to be ridden off-road with one hand while carrying a tray of noodles in the other.

“I love my Honda C90. Not because she is different, but because she is the world’s most popular motorcycle. This means two things; the first is the reason why she is the world’s most popular bike. The original design spec for the C90 said that it must be able to be ridden off-road with one hand while carrying a tray of noodles in the other.

“This means that anyone in the world can jump on one and ride off-road with no training, barefoot if they wish. It was also designed to be fixed by any mechanic with simple tools. Those two facts alone make it, to me, the most obvious choice for an adventure bike. But the main reason is what comes as a result of being the world’s most popular bike; spare parts. They are everywhere. Clutches, pistons, wheel bearings, spark plugs and tires, etc.

“Every time I meet an adventure biker on a large bike carrying spare tires, I always chuckle. If I think I can be cheeky and get away with it I ask, ‘Why do you carry spare tires?’ They usually reply, ‘You can’t get them out here.’ Then, in the least smug way possible I answer, ‘Maybe you should get a bike with the world’s most popular tyre size?’ I’ve had a variety of different responses but all admit the same thing. ‘If I had a C90, I wouldn’t need to carry all this extra weight of spare parts.’”

Ed March has a website, C90Adventures.co.uk, which is packed with the ups and downs of adventuring on his C90. You’ll also find a sliding scale of costs. C90 vs. bigger bike. Be warned, if you read it, you’ll be challenged, but also delighted at his frequently irreverent way of looking at life on the road. For example, would you put a reverse gear on your C90? Ed has just done so! He also has some amazing footage. Look out for the petrol tanker crash!

Lois Pryce

“Like everyone planning a long distance motorcycle expedition, my big question was ‘which bike?’ I knew I wanted some sort of off-road model as I expected to encounter a variety of terrains and road surfaces, but like many short riders, I found the seat heights of the popular overland machines off-putting. The XT225 Serow worked perfectly for the trip, in just about every way.” LoisOnTheLoose.com

Simon Gandolfi

“I chose the 125cc Honda for the journey—the original pizza delivery bike. I could buy it new in Mexico for $1,900. It’s built in Brazil, and spares are available throughout Hispanic America; it does 120 miles to the gallon; my legs have sufficient strength to hold it upright and I can lift it after a fall.”

Glenn Hall

American, Glenn Hall, is no author but has a real passion for motorcycles of any size. His love though, is anything old and bullet-proof that costs little to travel with, but allows him to go a very long way. Glenn’s latest trip on his 1969 Honda Trail was a 400 mile, five-day adventure through Baja California. “I didn’t need any spares and I rode up some of the steepest hillsides I’ve ever managed on a bike.” He, with yet another grin that seems to be a hallmark for these low CC riders, says he and his wife are the unofficial king and queen of the unofficial under 100cc touring club in the U.S. He adds wryly, “But you know, no one takes us seriously.” His advice for anyone planning a small CC ride? “Have fun, take lots of silly photos, be patient, and don’t try to rush! It’ll be the ride of your life!”

Who else is out there now?

In August of 2011 Irishman, Sean Dillon, set off to ride his Honda Cub from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego. A trip of over 20,000 miles, and at the time of this writing he’d made it as far as Costa Rica. He says, “I bought my bike on eBay for $1,000. Why this bike? It’s almost completely mechanical. No fuel injection, no water pump, no fancy engine management system, no catalytic converter and no electric start. They are all things that can’t be fixed by Joe Soap at the side of the road. The bike is defining my journey both in the actual limitations of travel but also in the experiences it offers. We’ve all heard the expression ‘using a sledge hammer to crack a nut,’ well this is the complete opposite end of the scale; this is like using your fingers to massage the nut until it slowly opens up and reveal its contents, with the inevitable addition of the sore fingers of course.

In August of 2011 Irishman, Sean Dillon, set off to ride his Honda Cub from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego. A trip of over 20,000 miles, and at the time of this writing he’d made it as far as Costa Rica. He says, “I bought my bike on eBay for $1,000. Why this bike? It’s almost completely mechanical. No fuel injection, no water pump, no fancy engine management system, no catalytic converter and no electric start. They are all things that can’t be fixed by Joe Soap at the side of the road. The bike is defining my journey both in the actual limitations of travel but also in the experiences it offers. We’ve all heard the expression ‘using a sledge hammer to crack a nut,’ well this is the complete opposite end of the scale; this is like using your fingers to massage the nut until it slowly opens up and reveal its contents, with the inevitable addition of the sore fingers of course.

“I did make a few modifications to the bike. I fixed on a basket so I can carry a couple of gallons of extra fuel, I’ve got a tank bag, I widened the leg shields for added protection, stuck on some basic panniers and wired in a USB power socket so I can charge my phone—which also doubles as my camera, etc.”

How’s the trip going? “Honda’s 1960s advert, ‘You meet the nicest people on a Honda’ is so true. It breaks down barriers between you and the local people; they see you as an equal, an underdog and not simply the rich gringo here to play in their country with their expensive toys.” HondavsTheWorld.com

Adventure traveller, Sam Manicom, spent eight years riding 55 countries and 200,000 miles around the world on his R80GS. He is the author of four acclaimed motorcycle travel books. Sam’s books are available in paperback, on Kindle, and his first book, Into Africa, is now available in audio format on iTunes. Sam-Manicom.com

Adventure traveller, Sam Manicom, spent eight years riding 55 countries and 200,000 miles around the world on his R80GS. He is the author of four acclaimed motorcycle travel books. Sam’s books are available in paperback, on Kindle, and his first book, Into Africa, is now available in audio format on iTunes. Sam-Manicom.com

Sticky logo

Sticky logo Search

Search