In seven weeks I’ve done 7,000 miles, most of them alone, not very impressive statistics for a truck driver. But I’m not a trucker anymore; I’m just a solo overland motorcyclist. All I’ve taken from my trucking days is an inherent sense of direction and a general contentment when being in my own company. I still have a dodgy load behind me, but it’s my baggage and I’m sure I need it all.

My own company is becoming a rare thing in Kazakhstan. Every car that passes (and there are many that pass my heavily laden KLR 650) have smiling faces, waving hands and phones pointing at me. This friendliness, intrigue and the open willingness to convey a sense of humanity consistently turns into hospitality whenever I stop and take off my helmet.

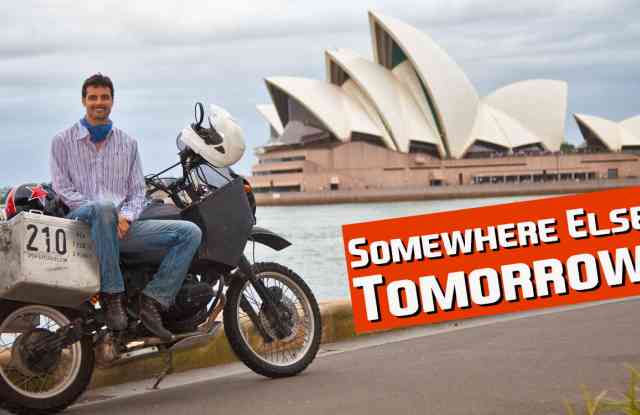

Solo travel and self-timing cameras, took 2 days to get this shot.

Solo travel and self-timing cameras, took 2 days to get this shot.

It begun at a parched and arid border crossing, with an enterprising kid selling bottles of frozen water, for a perfectly reasonable price. Not that I’m in any position to haggle—I’ve paid more for things I’ve wanted less. So, wet and sweaty all over but for a numb horizontal strip across my chest where the frozen water was stuffed inside my jacket, my introduction to Kazakhstan begins. I am instantly in a hostile desert, but hostility is limited only to the terrain.

The people are unassuming and have a generosity that raises my western warning levels of suspicion to avoid undesirable situations. It would appear that my self-preservation instinct is not needed in Kazakhstan—although that realization still doesn’t make it easy to relax it. With evidence of an increasing sense of security, I assess every situation for its falseness. There is none, the people here are as genuine as my momentary paranoia which slowly lapses into acceptance.

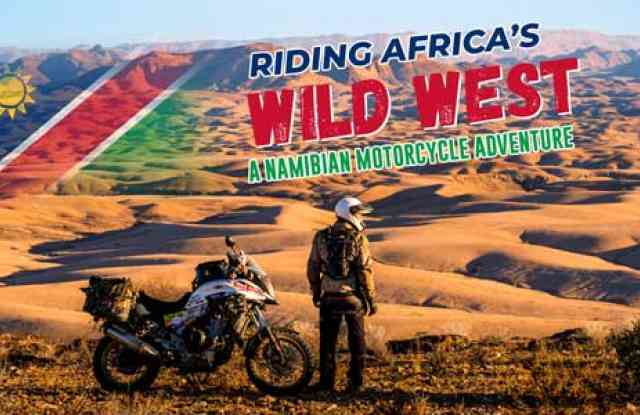

Stupid...stupid...stupid...I learned a lot of valuable lessons in one steeep learning curve.

Stupid...stupid...stupid...I learned a lot of valuable lessons in one steeep learning curve.

My first meal is in an open air bar, I was approached by a very drunk young man who insists he wasn’t mafia… well, I never suggested he was. He can get me anything I want, he has connections, thank you but I have Wi-Fi in my room and with that connection I too can get anything I want. He excuses himself, “I’m sorry I’ve been drinking for three days.”

“Really? I’ve been drinking since 1979, you’ll get used to it.”

I’m given a local phone and numbers to call, “in case of emergency,” by a man in a cafe whose concern for me I’m beginning to think is unnecessary. Three weeks into the country and that phone has vibrated invitations in Pigeon English texts and occasional checks on my wellbeing. I entered this country a stranger, no knowledge, no language skills and no connections; the reception I have received is not limited to this gifted phone.

I’m heading to Almaty, anywhere with warmth and views of snowy mountains is my idea of perfection. But two things that are bothering me: going south when I’m supposed to be heading east, and staying with people who do not speak English. However, the journey, any journey is all about new sights and experiences, so that is what I am going to do.

It would be easier not to but I know that staying with any native family, wherever I am, is a privileged insight into their everyday lives. A day in someone’s home is far more enlightening that a week in a hotel with a conducted tour every day. Sometimes it’s awkward, occasionally embarrassing, often confusing and always exhausting from being on best behaviour… but despite these difficulties, I feel the pang of loss as I say goodbye five days later—it’s like leaving home all over again. I was fed and trusted, treated not as a guest but as one of the family. The only thing I did to offend was to offer to pay my way.

I’m going to meet three Europeans—a Swiss and a couple of Austrians, whose common language is German; connections from the virtual overland community. We will ride north from Almaty together and see how it goes.

Sticky logo

Sticky logo Search

Search